LULLABIES

tenderness, frustration and shifting violence?

ONGOING

ARCHIVE

(under construction) - not-public - for documentation only

The central theme of this blog is lullabies and how they have changed throughout history. It is part of my ongoing artistic research focused on the exploration and revaluation of sleep, rest and dreams as creative triggers for music/sound composition.

First impressions

When I started fantasising about working with lullabies, my perception of them was sweet and tender. The first thing that came to mind was the memory of my great-grandmother singing me to sleep and this filled me with tenderness. When I began to learn more, and to dive into articles and books, digging into the origin and the historical and social function of these compositions, their meaning was transformed. I was impressed by how a big quantity of these "parenting songs" are mainly based on threats, risks and even death. The lyrics are usually borderline for the susceptible mind of a child, someone who is just learning about dangers, who does not yet clearly differentiate between fantasy and reality, even between dreaming and wakefulness.

Lullabies for gothic babies

My mother tongue is Spanish. I remembered that I got to know the English word "lullaby" ("nana"/"canción de cuna" =cradle song in Spanish) through the famous song by The Cure. With this funny association in mind, I reflect with other ears on the nostalgic and dark (kind of creepy…?) character that these songs have.

Lullaby by The Cure (1989)

On candy stripe legs the spiderman comes

Softly through the shadow of the evening sun

Stealing past the windows of the blissfully dead

Looking for the victim shivering in bed

Searching out fear in the gathering gloom and

Suddenly!

A movement in the corner of the room!

And there is nothing I can do

When I realize with fright

That the spiderman is having me for dinner tonight!

Quietly he laughs and shaking his head

Creeps closer now

Closer to the foot of the bed

And softer than shadow and quicker than flies

His arms are all around me and his tongue in my eyes

“Be still be calm be quiet now my precious boy

Don’t struggle like that or I will only love you more

For it’s much too late to get away or turn on the light

The spiderman is having you for dinner tonight”

And I feel like I’m being eaten

By a thousand million shivering furry holes

And I know that in the morning I will wake up

In the shivering cold

And the spiderman is always hungry…

When were the first lullabies sung? What were they about?

“The lullaby is certainly an ancient form of song, as mothers in all cultures instinctively croon to their babies to lull them to sleep.”

Excerpt From: Dan H. Marek. “Singing”

Directed song gives the infant a signal that the adult is paying attention to their needs, Mehr added. When singing, the adults cannot be talking to other people. The music also alerts the baby to the adult’s physical location.

“That’s information that can’t really be faked,”

coalition building and parent-infant signaling, provide compelling evolutionary reasons for the human development of music, the researchers said –and even makes the null-hypothesis, that music is “auditory cheesecake” and serves no purpose, less convincing.

“I don’t think we can completely dismiss the ‘auditory cheesecake’ hypothesis, but it really doesn’t offer a very compelling explanation for the entire package of evidence,”

https://news.wsu.edu/press-release/2020/10/26/war-songs-lullabies-behind-origins-music/

lull (v.): early 14c., lullen "to calm or hush to sleep," probably imitative of lu-lu sound used to lull a child to sleep (compare Swedish lulla "to hum a lullaby," German lullen "to rock," Sanskrit lolati "moves to and fro," Middle Dutch lollen "to mutter"). Figurative use from 1570s; specifically "to quiet (suspicion) so as to delude into a sense of security" is from c. 1600. Related: Lulled; lulling.

a song in a quiet tone with humming often has the effect of relaxing muscles and reducing blood pressure

Sleep therapy (self tranquilizing) and musical anaesthesia

The tone quality of a drum, combined with the humanistic science of thematic structures, can be self-applied to induce sleep. A drum with vibrant tone quality is needed, and must be played softly in a slow tempo. The ideal thematic structure should be simple, not rhythmically dense, and not more than one bar long in 12/8 or 4/4 time signature. Sleep therapy is best self-administered next to the bed. The structure of the theme and the tempo must not be varied. The short, open textured theme traps the mind in a recurring sonic loop that blocks off the intrusion of extraneous mental activity, and soon lulls the person to sleep. This simple science of inducing calmness and sleep by repeating a simple theme marks lullabies in African indigenous baby-soothing practice. In Africa, indigenous curative science greatly relies on musical anaesthesia, which is administered by a non-patient. It is encountered in some indigenous orthopaedic practices as an aid to bone-mending surgery, and also in the indigenous management or containment of insanity, whether innate or acquired. These are cases in which repetition of uniquely constructed structures is a conceptual forte in African musical arts science. The general principle remains to trap the mind in a revolving musical loop, and thereby sedate or banish the patient’s psychical presence as well as psychophysical sensations for as long as the sonic loop is circling.

From: A contemporary study of the musical arts – Volume 5 Book 1 Concert, education and humanizing objectives – theory and practice

motherhood: complaints and frustration in lullabies

The following text has been translated from "El gran libro de las nanas" by Carme Riera.

The great Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral wrote that the Lullaby is "a gift that the mother gives to herself and not to the child who can understand nothing". Despite my great admiration for the Chilean Nobel Prize winner, I disagree, in part, with her statement, since without a child to rock there is no lullaby. The gift, in any case, is for both, and it matters little that the child does not yet understand the meaning of the words. The lullaby, in which the voice that repeats sounds is fundamental, encourages him to fall asleep and the light rocking, in his mother's arms or in his cradle, helps him to calm down so that he can fall asleep.

The mother or whoever plays her role, cradling and singing a lullaby, is a kind of siren whose voice, perhaps unconsciously, tries to transport the child to a primordial and watery place, that is, to the maternal womb where for nine months he was preparing for the difficult task of having to start living outside his shelter, in another world less sheltered, more unprotected and harder.

Lullabies or lullabies have a soothing and perhaps even regressive purpose, to return to the unconsciousness of the womb, through sleep.

It is possible that the origins of lullabies, of multicultural and multilingual origin, are almost as remote as those of mankind and it is not difficult to imagine, thousands of millions of years ago, any of our ancestors in a cave or in a palafitte, squatting or standing, rocking her child, accompanied by the light murmur of some sounds, surely onomatopoeic, after discovering that swaying and murmur together have a greater effect in summoning sleep.

There is no doubt that lullabies are a poetic form linked to the lyrical tradition that is transmitted orally, related to the so-called songs of work and days, of which we have older samples than lullabies. Perhaps because, until the educated poets decided to compose them, it was women who created them, and as feminine creations they hardly leave the domestic sphere.

Let us remember that for centuries children passed, in a sort of continuum, from their mother's womb to the kitchen of their home or to the kitchen of their wet nurse's house. During childhood, years that did not count, without importance or history, children, as if they were still unfinished, remained under female guardianship, a circumstance that would further accentuate the fact that lullabies were understood as something without value, destined to the intimacy of the home and therefore without any transcendence. One was really born - but this only really happened to men, women were relegated to that interior space for life, with rare exceptions - when one passed from the domestic orbit to the exterior, which was reached after a rite of initiation that coincided with puberty.

If we hardly know anything about children's lullabies until practically the nineteenth century, it is because children remained linked to the feminine world, which was also uninteresting and consequently lacked history. Hence, many of the lullabies that women sang to their children have been lost since they were not fixed in writing. But there are others that have come down to us, thanks to songbooks and/or collections of carols, "converted to the divine", that is to say, sacralized by means of changes that change the profane sense into a religious one. In the case of lullabies, the passage from the profane to the religious is simple: the child that the mother tries to put to sleep is none other than Jesus and the lullaby is sung by the Virgin.

violence, death & fear themes

the analogy between death and sleep is an ancient one: for example, in Greek mythology the twin brother of Thanatos, the God of Death, is Hypnos, the God of Sleep

Lullabies with themes of death and violence toward the child are not found in every culture, but in some cultures, such as the Finno-Ugric and East Slavic, they are exceptionally common. These songs are often divided into mourning songs describing the death or funeral of the child, and threat songs which threaten the child with violence if he does not go to sleep. Threat songs are considerably more common than lullabies with death themes. (...) However, the content of many of the lullabies seems to be changing as higher standards of living, better nutrition, and a more secure future have evolved.

As with early societies, fear of the dark and its potential evils on a child seem to prevail in the words of most lullabies. The songs themselves are soothing but lyrics regarding danger, death, and even babies being stolen by thieves are common lyrics in not only the lullabies we know but also those that have been recovered from historical texts

one of the most famous lullabies (with many lyrics variations!):

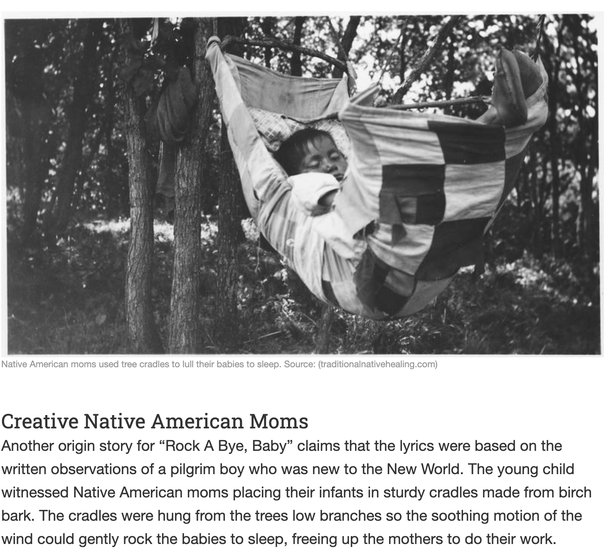

Rock a bye baby, on the tree top

When the wind blows, the cradle will rock.

When the bough breaks, the cradle will fall,

And down will come baby, cradle and all.

in Spanish language the most common text variation of Rock a bye baby is "Duérmete ñinx, duérmete ya" (in general said "niño" in masculine gender and here adapted to inclusive language as

"niñx").

duérmete niñx, duérmete ya

que viene el coco y te comerá

the English translation would be:

go to sleep child, go to sleep now

the coco ("bogeyman") is coming and will eat you

THE LEGEND OF "EL COCO"

(or “Bogeyman”, “Babau”, “Butzemann”,"Bubak" or "Hastrman", “Bala” ,Bussemanden", "Mörkö", "Torbalan", "The little man")

El Coco is a being that likes to scare children who do not want to sleep. His favorites are those who do not obey or who misbehave. The Coco likes to hide in the rooms of ill-mannered children, as well as in their closets, drawers and under the bed to scare them at night. There is another type of Coco that appears on nights when there is no moon. He puts lying children in a bag to turn them into soap. When a child does something wrong, he must apologise and accept his punishment, otherwise he will receive a visit from "El Coco". That is the only way to be saved from this malevolent being.

The appearance of the Coco varies in many places, he can be ghostly and with a head with three holes (two for his eyes and one for his mouth, like a coconut)

The expression coco is preferred in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Dominican Republic. In Portugal, Spain, Costa Rica, Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala and Venezuela it is known as coco. In Brazil it is used cuca, in Paraguay cucu.

Most of its names derive from a single word in English: booge, which has a link with goblins. In European culture around the 1500s, stories emerged about these characters, described as small men with beards and hair all over their bodies. According to mythology, these individuals lived in homes with their families but were only active at night performing different activities. The myth could then be born in the mouths of parents linking mythical beings with threats. In this way, the fantasy object took on a dark meaning, causing a greater impact on children.

https://www.ecured.cu/El_Coco_(criatura)

Lyrics translated from Icelandic Bíum bíum bambaló:

Bambaló and dillidillidó

My little friend

I lull to rest

But outside, a face looms at the window

When the mighty mountains

Fill your chest with burning desire,

I will play the langspil

And soothe your mind Bíum bíum bambaló,

Bambaló and dillidillidó

My little friend

I lull to rest

But outside, a face looms at the window

When the cruel storms rage

And the dark blizzard crouches above,

I shall light five candles

And drive away the winter shadows

Dodo Titit is a Caribbean lullaby that talks about a crab eating a baby. In Brazil, the lullaby Nana Nenê is about an alligator named Cuca that might get the baby if he or she stays noisy or cries. In Indonesia, an old lullaby of uncertain date reflects a roaming giant on the island that searches for crying babies.

Interestingly, in Japan, rather than scary themes, lullabies are often more melancholy, reflecting a mother longing or missing her child.

Lullabies such as Itsuki reflects a mother missing her child as she is away, although even here there is fear in the lullaby. In this case, the fear is if the mother dies then the dilemma might be who would take care of the baby.

In Malaysia, no harm happens to the baby but baby chicks seem to die in the lyrics during a count down of numbers. Overall, we see a kind of sad or depressing but often frightening theme to lullabies. This also could reflect the melancholy nature of many tunes.

Mosquitoes: a soft threat in Indonesian Lullabies

In Indonesian: "the word ninabobo is common translation for “lullaby.” The word comes from a mother that would chant softly to get their babies to sleep: Nina bobo, oh Nina bobo/kalau tidak bobo digigit nyamuk (Go to sleep, Nina, otherwise the mosquitoes will bite).

https://soundcloud.com/albert-juwono/nina-bobo-indonesian-lullaby

NANAS BOOKS